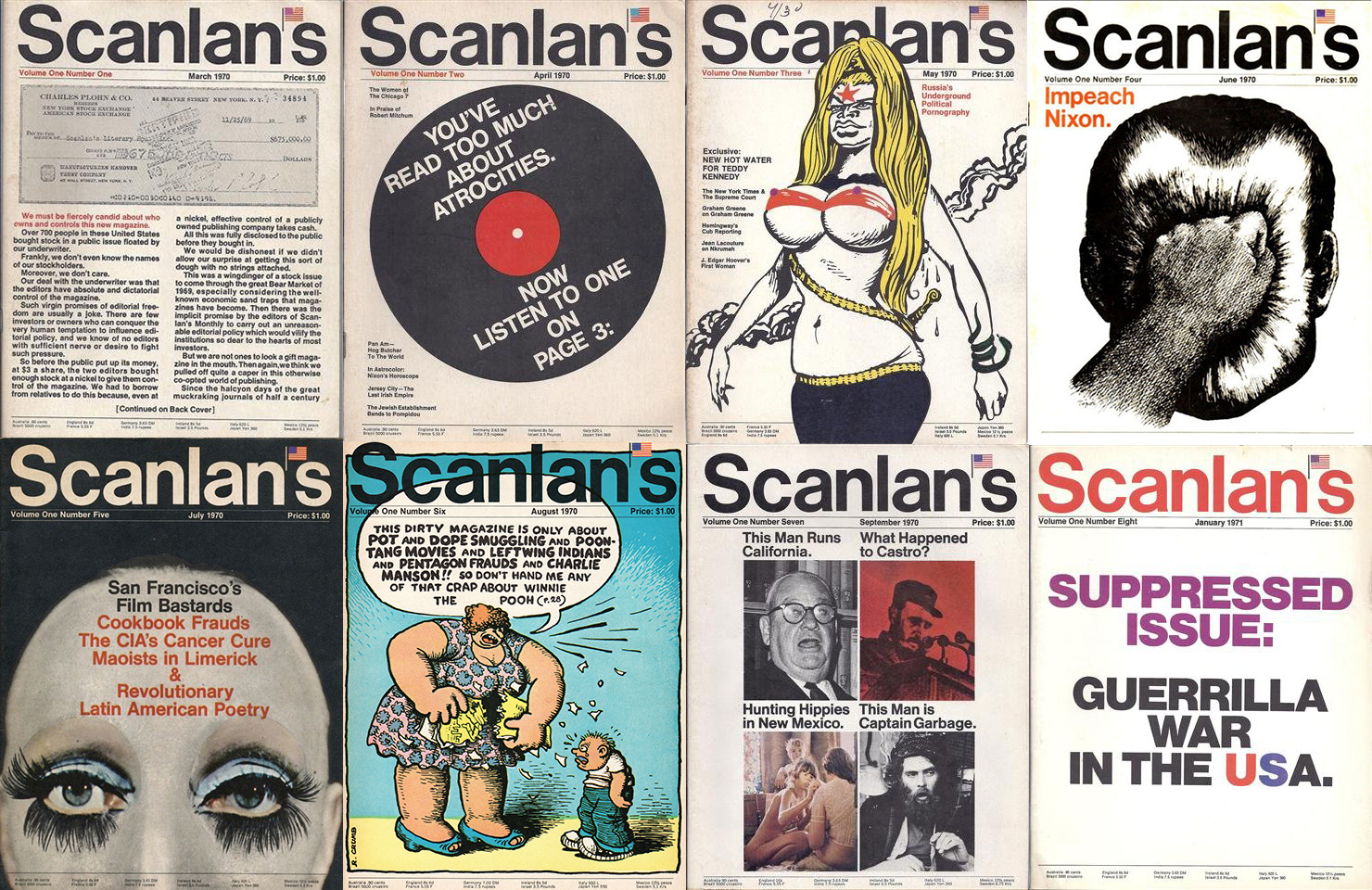

IN HIS 1976 MEMOIR If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade, former Scanlan’s Monthly co-editor Warren G. Hinckle III summarized Scanlan’s’ ten-month, eight-issue appearance on U.S. newsstands from March 1970 to January 1971:

During the short-lived Scanlan’s carnival I became engaged in [a] ridiculous battle with Spiro Agnew over the alleged pirating of a suspect memorandum from his office; was censored in Ireland; upbraided by the Bank of America for instructing love children how to counterfeit its credit cards; sued for one million dollars by the Chief of Police of Los Angeles; threatened by Lufthansa Airlines for an innocent editorial prank which they claimed cost them dearly, and also some other things happened.1

Few, if any, critics have accused Warren Hinckle of understatement during his consistently controversial forty-year career in journalism. But some of the “other things” that happened to Scanlan’s were extraordinarily atypical. Beside the curious events he described above, Scanlan’s was also subject to a nationwide boycott by lithographers and printers who refused to work on the magazine’s eighth issue and threatened to sabotage it because it was “un-American,” as well as the seizure of that same issue by Canadian police and U.S. immigration authorities. Scanlan’s also managed to infuriate President Richard Nixon, who requested an FBI investigation into Scanlan’s’ accusations against labor leaders whom Nixon invited to a meeting at the White House, a lawsuit against the magazine, and an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audit of Scanlan’s and its stockholders. If a magazine’s achievements can be measured in part by whom and how many it infuriated in the shortest amount of time, then surely Scanlan’s deserves to be honored.

In the midst of such special attention, Scanlan’s managed to print some of the most provocative muckraking journalism of its time. It tackled a bewildering array of topics: Vietnam atrocities, the murder of a member of the Black Panther party, Mexico–U.S. marijuana smuggling, CBS’ role in a failed invasion of Haiti, Mark Twain, the environment, Charles Manson, Russian pornography, the Mafia, counterfeit credit cards, and domestic guerilla warfare, among others. Scanlan’s also published the first examples of Hunter S. Thompson’s now-celebrated “Gonzo journalism,” and two years before anyone outside of Washington, D.C., had heard of Watergate, Scanlan’s called for President Nixon’s impeachment.

Scanlan’s Monthly was largely the byproduct of the adventurous, agitating, publicity-seeking, and hard-drinking personality of Hinckle.2 In the late 1960s, he was well-known as the notorious editor of Ramparts magazine, America’s leading publication of the left. He first began working with Ramparts in the early 1960s as a publicity man and to this day has never lost the ability to create a sensation. By 1965, twenty-six-year-old Hinckle had become executive editor and associate publisher of Ramparts and, according to Time, had transformed the magazine “from a mediocre Catholic literary quarterly into a rampaging crusader for leftist causes.”3 Under Hinckle, Ramparts was a tireless muckraker, exposing the CIA’s secret funding of the U.S. National Students Association, linking secret Michigan State University research with the CIA, and printing the disclosures of a former Special Forces sergeant who was taught methods of torture in Vietnam. Ramparts was a firebrand critic of the Vietnam War, and the magazine’s full-color, provocative covers often conveyed its opposition to the war as well as its articles and editorials did. Its December 1967 issue depicted four unidentified hands each clenching a burning draft card bearing the name of a Ramparts editor; one, of course, bore Hinckle’s name.

The cover caused such a stir that the four editors were called before a federal grand jury for alleged violations of Selective Service laws in June 1968, but the charges were eventually dropped.4 The magazine’s photography also packed a punch. An issue of Ramparts that featured several photos of a Vietnamese mother and her lifeless baby, killed by American bombs, helped inspire Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to publicly announce his opposition to the war.5

Ex-Ramparts editor Peter Collier captured the style of Ramparts-era Hinckle, if not his substance, in his book Destructive Generation:

Hinckle liked to think of himself as an old-fashioned newspaperman, a heavy drinking, muckraking troublemaker in the tradition of Ambrose Bierce and Citizen Kane. . . . [H]e was almost comically anxious to acquire panache and cultivated a dandy’s style that emphasized patent-leather dancing pumps and three-piece suits. . . . His trademark was a patch covering a missing or mutilated eye, whose fate remained a mystery. My son Andrew, then three years old . . . referred to Warren as “that pirate guy.” This was closer to the truth than he could have known, as the investors Hinckle convinced to put a king’s ransom into Ramparts over the next few years could have ruefully affirmed.6

Indeed, Hinckle’s ability to raise money for Ramparts, often from bizarre sources, was as legendary as his ability to spend it. He enticed college professors, a retired inventor, and a jailed mobster to invest in Ramparts.7 Nor was he known for his frugality; once, when stranded in Chicago and unable to fly to New York because of a domestic air strike, he chose fly to London, and once there, purchased a seat on a London-to-New York direct flight.8

Hinckle’s personal spending habits surely ate away at the Ramparts coffers, but it was his editorial decisions that helped to empty them. For example, he did not hesitate to take a Ramparts contingent to Chicago in August 1968 to cover the Democratic national convention. There, Hinckle and his staff printed a “daily broadsheet” that cost the magazine $50,000, of which $10,000 was for the staff’s hotel suite alone.9 While the excursion may have contributed to Ramparts’ slide toward bankruptcy, it helped plant the seed for Scanlan’s. Also in Chicago that week was Sidney Zion, a New York Times law reporter who had written both for Ramparts as a freelancer and about Ramparts for the Times. He and Hinckle first met in New York in 1967 and hit it off instantly. Zion wrote about their immediate rapport in his 1982 book, Read All About It!: The Collected Adventures of a Maverick Reporter. “We hit it off great; we clicked just like that,” Zion wrote. “It was more a matter of style than substance, as it turned out, but the style was so similar that for years it seemed to cover our real differences. . . . Mainly, it was the bar scene we had in common. Hinckle and I love a great bar. It’s our court.”10

In Chicago, Zion learned from Hinckle that Ramparts was “just about tapped out,”11 and the two began discussing ideas for a new magazine. But before Hinckle could dive into a new venture, he first had to divorce himself from Ramparts. His departure would be controversial, but controversy seemed to follow Hinckle wherever he went.

By January 1969, Ramparts was on the brink of bankruptcy.12 In New York, Hinckle told a group of magazine editors not to “pay much attention to those stories about Ramparts’ troubles,”13 yet only a few days later in Ramparts’ San Francisco offices, he suddenly reported that the magazine was bankrupt. He resigned as editor and president on January 29, and shortly thereafter Ramparts’ board of directors declared bankruptcy.

But Hinckle did more than just announce his resignation from Ramparts on January 29; he also told reporters that he had been offered and had accepted financial support for a new magazine to be called Barricades. He added that the first issue of Barricades would appear February 25. This bit of information led The New York Times to conclude that “plans for the new publication had been under way for some time.”14 Hinckle’s abandonment of the Ramparts ship did not thrill publisher Frederick C. Mitchell, who probably spoke for other bitter Ramparts staffers when he sarcastically told the Times, “[W]e know [Hinckle] must be weary from having tried so hard to raise money.”15

Barricades’ first issue did not appear on February 25, 1969; in fact, it would be a year before Hinckle’s new magazine would appear on newsstands. Through the winter and spring of 1969, Hinckle and Zion struggled to find investors for the magazine and managed to raise only $50,000. They soon decided on a new idea: to take the magazine public. The first day Barricades stock was issued, its price soared from $3 to $4.50. In November 1969, Charles Plohn & Co., the magazine’s underwriter, presented Barricades’ editors with a check for $675,000.16

Hinckle, thirty-one, and Zion, thirty-five, now had the money they needed to start their magazine, but it had a new title: Scanlan’s Monthly. The title “honored” John Scanlan, an Irish pig farmer described by a group of “old IRA guys” that Zion and Hinckle came across while touring Ireland in 1968 as “the worst man who ever lived in Ireland”—the father of seven illegitimate children that he neither raised nor supported.17 In late February 1970, Scanlan’s Monthly finally debuted. Its first issue featured the $675,000 check from Charles Plohn & Co. on its front cover, along with an editorial manifesto spanning the front and back covers which read:

Since the halcyon days of the great muckraking journals of half a century past, there has not been one publication in this country whose editors were absolutely free—and had the cash—to do what journalists must do. That vision of a free, crusading, investigative, hell-raising, totally candid press has largely been consigned to the apologias of the smug publishers who won the working journalists and to the barroom daydreams of newsmen. . . . Scanlan’s eschews the reliance on any outside economic force—including that almost irresistible mistress advertising—and will charge the reader enough to make it on circulation alone. . . . In the meantime we have enough money to sustain ourselves and to print exactly what we want. . . . We will make no high-blown promises about how great this magazine is going to be. Pay the buck and turn the page.18

Once they paid the buck and turned the page, readers quickly got a taste of Scanlan’s’ muckraking, hell-raising content. Articles in the first issue included Gene Grove’s expose of CBS’ role in the failed invasion of Haiti by Haitian refugees; a veteran’s account of atrocities committed by U.S. soldiers in Vietnam; an investigative report on the cleanliness of New York restaurants by New York Post writer Joseph Kahn; Sol Stern’s account of a disastrous Rolling Stones concert at Altamont Raceway in California where a concertgoer was stabbed to death by Hell’s Angels; a piece by Richard Severo on Alabama’s Cajun population; excerpts from Ben Hecht’s book about gangster Mickey Cohen; and even something for comics lovers, “The Adventures of Tintin.” Of course, Scanlan’s would not have been complete without an editorial section. Titled “What Obtains?” it included biographies of Scanlan’s’ editorial staff (managing editor Donald Goddard was described as “a goddam Englishman”), under the heading “Who Are We to Make a Magazine?”19 “What Obtains?” also featured the editors’ defense of the right of reporters to protect their sources, and a review by Israel Schwartzberg, “the underworld’s foremost authority on the underworld,”20 of a book about the Mafia.

Volume One Number One’s robust mix of muckraking journalism, literary criticism, film reviews, and photographic essays was widely reviewed in mainstream newspapers and magazines, including The New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and Commonweal. Henry Raymont’s February 25, 1970, New York Times article described Scanlan’s’ strategy to shun advertising in order to maintain its editorial independence. “Unlike other national magazines that are desperately struggling for the advertising dollar,” Raymont wrote, “Scanlan’s is pledged to operate on the principle of the penny press—wherein a publication proves its mettle by letting circulation foot the bills.”21

Scanlan’s was widely criticized for what reviewers believed were alarmingly lax editing standards. Peter Steinfels wrote in Commonweal:

Perhaps it is in the tradition of barroom journalism to paste your publication together late in the night in some ill-lit speakeasy, thus overlooking those finer points of makeup that indicate where one section of the magazine ends and another begins, what is text and what is caption, and so on. . . . If that is the case, then Scanlan’s is certainly true to the tradition.22

The March 9 issue of Time seemed to confirm Steinfels’ suspicion that Scanlan’s was put together in boozy, haphazard circumstances. The New York office, located in midtown Manhattan at 143 West 44th Street, was described by Time as “sandwiched between a dilapidated Irish pub and a skin-flick cinema.”23 Inside, Time discovered chaos: cluttered desks and typewriters, freelance writers demanding payment, and private investigators in deep conversation with editors.24

Hinckle proudly told Time, “We did everything we weren’t supposed to. No marketing studies. No direct-mail campaigns. No promotion. No ads. We didn’t even do a dry-run issue.”25 Like Commonweal, Time felt that one of the things Scanlan’s was not supposed to do was edit in such a sloppy fashion, singling out Grove’s CBS/Haiti article as an egregious violator of proper editing standards. Time added that Hinckle’s and Zion’s copy on the cover of the issue read “like an ultimatum.”26

Hinckle’s reputation as a financial profligate preceded him, and Commonweal’s Steinfels eagerly reported that Hinckle spent $300,000 of the original $675,000 before the first issue had even appeared on newsstands. He then added uncharitably, “I wonder what his next idea for a magazine will be,” referring to Hinckle’s controversial departure from Ramparts.27 Hinckle’s ability to spend money was well established by this point, but Zion readily admitted in Read All About It! that he was no miser himself. While Zion wrote, “Nobody spent other people’s money like Warren,” he also conceded, “I have no taste for accounting, either, and I’m a pretty good spender. It wasn’t all Hinckle.”28

Hinckle and Zion may have spent a little less than half of their seed money by Scanlan’s’ debut issue, but they were expecting to issue a second public floatation of stock in order to raise more money. This plan did not pan out due to the crash of the new issues market, which eventually led to Charles Plohn & Co.’s demise.29 Despite the absence of a second influx of cash, Zion claimed that both editors were dedicated to putting out a high-quality magazine, willing to pay writers far more than the going rate, and ready to buy a first class ticket anywhere in the world for a reporter covering a story.30 Zion explained the magazine’s editorial and financial philosophy in Read All About It!: “Nobody could keep a national magazine afloat on $675,000, unless it were run on butcher paper and a close-to-the-vest budget,” Zion wrote. “Well . . . we wanted a big, exciting book with plenty of four-color journalism and artwork. So butcher paper was out, and of course so was budgeteering.”31

The name most commonly associated with Scanlan’s today is not Zion or even Hinckle, but Hunter S. Thompson. In 1970, Thompson was a thirty-two-year-old freelance writer best known for his 1966 book, Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga. Hinckle first met Thompson in San Francisco in 1966, and as he would with Zion, immediately discovered a common love for the bar scene.32

In late 1969, Hinckle agreed to publish Thompson’s article about celebrated French skier Jean-Claude Killy that Thompson had originally written for Playboy. The article was indignantly rejected by Playboy; one editor was so angered by it that he composed an internal memo which declared, “Thompson’s ugly, stupid arrogance is an insult to everything we stand for.”33 But Scanlan’s was not Playboy, and Hinckle was thrilled with the article, a long and rambling story about an Olympic gold medalist who now spent his time promoting Chevrolet automobiles. “The Temptations of Jean-Claude Killy” went far beyond the accepted rules of objective reporting and placed as much emphasis on Thompson’s own role in the story as it did Killy’s.

Douglas Brinkley, the editor of two collections of Thompson’s letters, has stressed “how important a role the editor of Scanlan’s Monthly, Warren Hinckle, played in the development of Thompson’s infamous Gonzo style.”34 Thompson told Playboy, the same magazine that once rejected his submission, that Hinckle was “the best conceptual editor I ever worked with.”35 Indeed, Hinckle’s enthusiasm for Thompson’s unusual brand of journalism provided the latter the opportunity to publish articles that few other magazines would. Thompson, who once defined Gonzo as “a style of reporting based on William Faulkner’s idea that the best fiction is far more true than any kind of journalism,”36 would take the style to new heights a few months later, again in the pages of Scanlan’s.

While Thompson’s work is now widely praised, at least one contemporary critic was unimpressed. Commonweal’s Steinfels slammed the piece, writing that the article “is so bad that Playboy looks good” for rejecting it.37

In a January 12, 1970, letter to his friend, author William J. Kennedy, Thompson wrote that he was optimistic about the future of Scanlan’s. “The first issue is due in March, and I assume it will be something like the old, fire-sucking Ramparts,” Thompson wrote. “If their taste for my Killy article is any indication, I’d say it will be a boomer. . . . Hinckle has weird and violent tastes.”38

Hinckle’s “violent tastes” were evident in the April 1970 issue of Scanlan’s. The cover read, “You’ve Read Too Much About Atrocities. Now Listen to One on Page 3.” The eighty-page issue included a bound-in record containing testimony from the court-martial trial of an Army lieutenant who was charged with deliberately killing a South Vietnamese soldier. April’s issue also featured articles about the influence of the Mafia in Jersey City, New Jersey; a Studs Terkel piece about the wives and girlfriends of the jailed Chicago Seven; Pan Am Airlines’ role in U.S. military interventions; an astrological portrait of President Nixon; and a second installment of the “Dirty Kitchens of New York” series.39 In “What Obtains?,” the editors attacked both Arab terrorists and Jewish-American organizations and also outlined their letters policy, which charged writers 25 cents per word, or $1 per word for letters “which we find particularly dumb, boring or offensive.”40

But it was not an article or editorial from April’s issue that attracted the most attention; instead it was an advertisement—or what appeared to be an advertisement—for Lufthansa Airlines on the back cover.

The doctored advertisement was created and sold by a freelance writer to Scanlan’s for $50 and used the original copy (which featured the tag line “This year, think twice about Germany”) and photographs, with two notable exceptions. One “replacement” photograph showed a nude woman with her hands bound behind her back being whipped by a soldier, while a third person filmed the scene; another showed three Nazi Luftwaffe soldiers giving “Heil Hitler” salutes. In the May issue of Scanlan’s, the editors re-printed an Advertising Age article in which Zion said the advertisement was a “natural” for Scanlan’s because “it seemed awfully odd for Lufthansa to be using a line like, ‘think twice about Germany.’ When they invite second thoughts, this is what can happen.”41

When it was not busy printing doctored versions of legitimate advertisements in its own pages, Scanlan’s was doing its own advertising. On May 10, an eye-catching, full-page advertisement bearing the headline, “YOU TRUST YOUR MOTHER BUT YOU CUT THE CARDS,” appeared in The New York Times, and the advertisement was run again four days later. The tongue-in-cheek, irreverent copy described who ran Scanlan’s, the magazine’s mission, and past, present, and future articles. “You could think of SCANLAN’S as a cross between Ramparts and The New York Times,” the advertisement read. “You’d be dead wrong, but you could think of it that way if you wanted to.”42

The same month that the “You Trust Your Mother” advertisements first appeared, Zion told Newsweek that Scanlan’s was selling 75,000 to 80,000 copies of each issue but needed to sell more than 110,000 to break even.43 It’s possible Scanlan’s expected its June 1970 issue to reach the 110,000 circulation mark; its attention-grabbing cover featured an illustration of President Nixon’s face with a fist firmly planted in it, under the headline “Impeach Nixon.” The editorial in the “What Obtains?” section accused Nixon of high crimes, misdemeanors, and “outright fraud” including the undeclared invasion of Cambodia, as well as the “rape of the stock market, mayhem on the economy, and felonious assault on the Supreme Court.”44

The June issue also included a “how-to” article on counterfeiting credit cards and getting away with it, complete with step-by-step photographs.45 Also included was a piece on the murder of Black Panther Fred Hampton by Chicago police, an examination of the advertising industry’s appropriation of environmentalist imagery, and an insider’s look into Newsweek magazine by a former staff member.

June’s issue was also notable for Thompson’s “coverage” of the annual Kentucky Derby horse race in Louisville. Thompson originally asked Hinckle to hire Denver Post editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant, a Pulitzer Prize winner, for the article, but when he proved unavailable, Hinckle flew in thirty-four-year-old Ralph Steadman, a Welsh illustrator acclaimed in the United Kingdom for caricatures of British politicians. According to Brinkley, the “combustible pairing” of Steadman and Thompson “changed the face of modern journalism.”46 “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” matched Thompson’s “viciously funny, first-person, Gonzo perspective” with Steadman’s “perversely exact illustrations . . . drawn in lipstick to shock the unprepared reader. The outrageous, ribald result won immediate acclaim.”47

The article was written by Thompson while “locked in [a] stinking hotel room with a head full of pills & no sleep for 6 days, working at top speed & messengers grabbing each page out of the typewriter just as soon as I finished it.”48 The result was antithetical to traditional sports coverage, chronicling Thompson’s and Steadman’s alcohol- and drug-fueled (and mace-infested) escapades in Louisville while somehow managing to debunk a celebrated American tradition:

“[Thompson:] Hell, this clubhouse scene right below us will be almost as bad as the infield. Thousands of raving, stumbling drunks, getting angrier as they lose more and more money. By midafternoon they’ll be guzzling mint juleps with both hands and vomiting on each other between races. . . . The aisles will be slick with vomit; people falling down and grabbing at your legs to keep from being stomped. Drunks pissing on themselves in the betting lines. Dropping handfuls of money and fighting to stoop over and pick it up.” [Steadman] looked so nervous that I laughed. . . . “Don’t worry. At the first hint of trouble I’ll start pumping this ’Chemical Billy’ into the crowd.”49

The article helped catapult Thompson toward celebrity status. Soon, his Gonzo journalism would appear regularly in Rolling Stone and in best-selling books. “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” may have been a roaring success, but Thompson’s optimism about the future of Scanlan’s had faded. In a May 15 letter to Hinckle, he wrote:

As for Scanlan’s general action . . . well, what little I saw of the NY scene leaves me slightly worried. Something is badly lacking in the focus, the main thrust—and $10,000 ads in the NY Times only emphasize what’s missing. . . . [T]he vibes I got in NY were somewhat mixed—and the only cure I can see is impossibly drastic.

The fucker should work. It’s one of the best ideas in the history of journalism. But thus far the focus is missing—or maybe it just seems that way to me; perhaps something missing in my own focus.50

Thompson was not Scanlan’s’ only critic that month. In the May 25 issue of Newsweek Lee Smith lamented, as Time and Commonweal had in March, Scanlan’s’ untidy editing. He believed that “nobody seems to have to exercised much control over the three issues that have appeared so far.”51 His conclusion was fairly damning: “[U]nlike Ramparts, which attracted attention to itself with explosive exposes, Scanlan’s has not created a public scandal, an unhappy condition for a muckraking magazine.”52 Smith also suggested Scanlan’s was suffering from internal strife, describing managing editor Goddard’s imminent departure as well as the problems posed by Hinckle being in New York only ten days a month. Smith quoted one anonymous staffer: “Warren creates a Gotterdammerung [marked by catastrophic violence and disorder] atmosphere in which he will go down as the misunderstood genius.”53 In Lemonade, Hinckle conceded that his decision to spend most of his time in San Francisco created friction between himself and Zion. “The chemistry that made my friendship with Zion did not serve to make a magazine,” he wrote. “Scanlan’s became an East Coast-West Coast tug of war.”54

But then again, nothing brings a magazine’s staff together like calling the vice president of the United States a liar in print. In a July 22 New York Times article published six days before Scanlan’s’ August issue hit the newsstands, James M. Naughton reported that the August issue featured a memorandum dated March 11 (labeled “page 2 of 4 pages”) linking Vice President Agnew with a report allegedly written by the Rand Corporation.

The memo appeared to confirm the existence of a report by Rand that analyzed the possibility of canceling the 1972 presidential election and repealing the Bill of Rights. The document also mentioned the use of CIA funds to inspire “spontaneous demonstrations” supporting Nixon’s Indochina policy by construction workers in several U.S. cities.55

Agnew, whom the Times allowed to preview Scanlan’s’ August issue so he could comment, said it was “ridiculous” that the magazine believed the memo was authentic. Agnew added that the letterhead used in the Scanlan’s memo was different from what was used by his office. “My denial is unequivocal,” Agnew said.56

Zion told the Times that the memo came from “a source who had never misled him in the past,” but he did not disclose who it was.57 “The document came directly from Mr. Agnew’s office, and he knows it,” Zion said.58 Scanlan’s further answered Agnew’s denials on July 30 and again on August 2 with a full-page advertisement in The New York Times titled, “THE FAMOUS AGNEW MEMO.” In it, Scanlan’s expressed surprise that Agnew would “get quite so livid” or “so picayune,” and said it was “pleased to submit our credibility against his.”59

In its Fall 1970 issue, Columbia Journalism Review criticized Scanlan’s for making “little effort to establish any authenticity for the document; in a news story the editors merely remarked that the item was a source that had never misled them.”60 CJR then repeated Scanlan’s’ statement submitting its credibility against Agnew’s, but it concluded, “It’s not a choice a reader wants to make on faith alone.”61

The Agnew memo did more than prompt Columbia Journalism Review to reprimand Scanlan’s in print—by July, it also had attracted the attention of the White House. John Dean, former White House counsel to Nixon, revealed as much in his 1976 memoir Blind Ambition.62 On July 24, 1970, his first day of work at the White House, thirty-one-year-old Dean was handed a confidential memorandum with specific instructions: “It was noted that [Scanlan’s’ printing of the memo] was a vicious attack and possibly a suit should be filed or a federal investigation ordered to follow up on it.”63 After consulting with members of the White House staff, Dean learned that the person who described Scanlan’s’ printing of the memo as a “vicious attack” was none other than President Nixon. Dean was “astounded” that Nixon was “so angrily concerned about a funny article in a fledgling magazine.”64 He then sent the president a memorandum on August 4, 1970, which warned against a lawsuit or FBI investigation. On that memo, Nixon hand wrote, “H—Have I.R.S. conduct a field investigation [on Scanlan’s] on the tax front.”65

Soon after receiving instructions to proceed with an IRS investigation of Scanlan’s, Dean met with an acquaintance and complained, “I’m still trying to find the water fountains in this place . . . [and] [t]he President wants me to turn the IRS loose on a shit-ass magazine called Scanlan’s Monthly.”66 Dean then turned to White House staffer John J. Caulfield, who discovered that a tax inquiry on Scanlan’s was fruitless because the magazine was only six months old and had yet to file a tax return. However, Caulfield asked the IRS to look into the tax records of Scanlan’s’ owners. Dean wrote in Blind Ambition that he had no idea how Caulfield was able to get the IRS to agree to act so easily nor did he discover what became of the IRS inquiry.67

What Dean did not know was that the IRS commonly undertook investigations for political reasons upon the request of the FBI, the CIA, and the White House. Investigations by the U.S. Senate’s Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (commonly known as the “Church Committee” in reference to committee chairman Frank Church, an Idaho senator) in 1974 and 1975 determined that the IRS investigated individuals, organizations, and publications, including magazines such as Ramparts, Playboy, Commonweal, Rolling Stone, and The National Observer.68

A month later, Dean found himself dealing with Scanlan’s once again. The magazine ran a full-page advertisement in the September 15 and 20 editions of The New York Times titled “The Great White House Tea Party.” The advertisement featured a photograph of President Nixon in a meeting with four construction union leaders and accused the union bosses of various crimes and indiscretions, including extortion, racketeering, and running a nearly all-white union. The advertisement for the September issue included a summary of Scanlan’s’ previous contents and repeated the “You Trust Your Mother” motto, underneath which the copy declared, “In seven months we’ve cut the cards on a lot of mothers.”69

Back at the White House, Dean was told to have the FBI check into Scanlan’s’ charges that the labor leaders with whom Nixon had met were “shady characters.”70 But shortly afterward, Dean wrote, “Scanlan’s went out of business, its editors unaware of how much trouble they stirred up at the White House.”71

During that summer and fall of 1970, Scanlan’s had no inkling that the White House was busy investigating its claims or ordering the IRS to investigate its owners. The magazine was holding its own; Zion recalled in Read All About It! that Scanlan’s looked as if it was going to make it, “despite our spending habits.”72 There is little evidence to suggest that anyone at Scanlan’s believed it was on the brink of extinction; Hinckle and Thompson had agreed on a series of monthly articles titled “The Thompson-Steadman Report” that would debunk American institutions such as the Kentucky Derby, Mardi Gras, the Super Bowl, the America’s Cup sailing races and other events.73 Sadly for Scanlan’s, its eighth issue would be its last.

Months before the October 1970 issue was due to arrive at newsstands, Scanlan’s staffers were busy at work on the issue, which was devoted entirely to “Guerilla Warfare in the U.S.A.” According to Zion, the issue “was Hinckle’s baby, and the core idea was to document acts of sabotage and terrorism in the country going back to 1965.”74 It included a thirty-two-page section that documented approximately 1,500 incidents of bombings, sabotage, and terrorism in the U.S. during the previous five years.

The difficulties which eventually led to Scanlan’s’ demise began when the 116-page issue was sent to Barnes Press, a New York City printing company that Scanlan’s was contracting with for the first time.75 On October 3, The New York Times reported that members of the Amalgamated Lithographers of America who handled lithographing duties at Barnes refused to process the magazine on the grounds it was “un-American” and “extremely radical.”76 In particular, the lithographers objected to the issue’s “What Guerillas Read” section, which featured American “guerilla propaganda” from both extreme right-wing and left-wing groups, and included instructions for the construction of a bomb from a Colorado-based right-wing periodical.77

Zion quickly held a press conference in Scanlan’s’ New York office and told reporters that the lithographers’ actions were “paranoid” and a violation of the First Amendment. “The assertion they make is so brazen—that they have the right to say what’s printed in this country,” Zion said.78 The Times also reported that Barnes Press offered to take back the magazine to have it printed after Barnes had reached an agreement with the president of Amalgamated Lithographers of America. However, Scanlan’s declined the offer because, according to Zion, the financial terms were not the same as those agreed upon before the dispute.79

Two days later, Scanlan’s filed suit against Barnes, demanding it print the issue under the original terms of the contract. In the interim, Scanlan’s searched for another printer and found a San Francisco-based press that agreed to handle the issue. Yet when Scanlan’s sent a check to the company as a binder, it was returned without explanation. Later that month, Scanlan’s reached an agreement with Medallion Printers and Lithographers of Los Angeles to print the guerilla warfare issue and future issues. However, president Larry Narry of Medallion telephoned Scanlan’s managing editor, Tom Humber, in New York to inform him that he could not print the issue because union workers at the plant called the issue’s content “un-American” and threatened to sabotage the issue if forced to work on it.80 At an October 22 press conference in New York, Zion told reporters that San Francisco police told a Scanlan’s contributing editor, Earl Shorris, that the magazine would never again receive press credentials if the issue in question featured illustrations of how to make bombs. Meanwhile, Scanlan’s was told that lithographers employed by three printing companies in Denver and one in Missouri refused to work on the issue. Managing editor Tom Humber told Publisher’s Weekly that by the end of October the delays had cost the magazine $100,000 at a minimum.81

Later that fall, Scanlan’s finally found a printer, albeit one in another country: Payette-Simms Co. Ltd. of St. Johns, Quebec. On December 10, 6,000 copies of what was now titled the January 1971 issue were seized by U.S. customs agents in distributors’ warehouses in San Francisco and Oakland after arriving from Quebec, but the issues were then ordered returned to the warehouses without explanation. The order calling for the seizure cited a possible violation of U.S. law prohibiting importation of “materials advocating treason or forcible resistance to the nation’s laws.”82 On the same day that U.S. customs agents were seizing copies of Scanlan’s in California, Montreal police seized 80,000 copies of the issue at the printer’s warehouse, while another 22,000 copies were seized from a truck en route to the U.S. In Read All About It!, Zion claimed that Montreal police told the Canadian media that U.S. authorities requested the seizure. “[Canadian Broadcasting Corporation] radio asked the chief of police of Montreal why,” Zion wrote. “He said, ‘The United States Government asked us to stop it.’”83

Zion told The New York Times on December 11 that the seizures were made “in collusion with the United States government,”84 while Montreal police told the newspaper that the seizures were made because Scanlan’s lacked a proper printing registration.85 The magazine finally received the proper registration (with the condition that it not be sold in Canada), but the binder with which it had contracted now refused to work on the issue, and soon afterwards Scanlan’s’ national distributor dropped the magazine. What’s more, news dealers in thirty cities, including Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, refused to stock this issue. Zion claimed that he spoke with anonymous news dealers who said “government officials” had visited them personally and told them that selling Scanlan’s wasn’t good for the country or for the news dealer.86

Time reported in January that several printers claimed they had refused to print the issue because of uncertainty about Scanlan’s’ financial status, not because of its contents. However, Time also reported that a business information service, Dun & Bradstreet, said the magazine’s net worth was $497,976.87 In Read All About It!, Zion claimed the press ignored Scanlan’s’ problems because of rumors about its shaky finances.88 Despite Zion’s claims, Scanlan’s travails were covered by a largely supportive mainstream press, including a few magazines which had not reviewed the magazine positively months before. A Publisher’s Weekly editorial read:

If the staff at Scanlan’s is feeling a bit paranoid . . . it has good reasons. . . . [W]hat is involved in the Scanlan’s case is censorship not on moral but on political grounds. . . . If a publisher can be systematically denied access to the means of communication, freedom of the press is destroyed.89

Columbia Journalism Review and The New York Times also printed similar editorials supporting Scanlan’s and accusing those who had refused to work on the issue of censorship.90

The January 1971 issue of Scanlan’s finally hit New York newsstands on January 14, and Scanlan’s’ managed to organize a makeshift distribution scheme in some parts of the U.S.91 Because of the delays, the issue was printed on cheap butcher paper, excepting the cover, which declared in stark, bold print: “SUPPRESSED ISSUE: GUERILLA WAR IN THE U.S.A.” On page one, under a headline reading, “WE’VE MOVED TO CANADA,” Scanlan’s explained why it had “fled” the U.S.:

[Canada’s] atmosphere is eminently more conducive to the publication of Scanlan’s than the hardhat state of America. Here, printing plants in states from coast to coast knuckled under to sabotage and other blackmail rather than print Scanlan’s. . . . This issue tells the truth of what is going on in this country. Some ruffian printers decided they didn’t want the truth printed. . . . Subsequently, Scanlan’s has been turned down by other large printers in Colorado and Missouri. Their reason: the lithographer’s union had “put the word out on Scanlan’s.” Any printer who had tried to print the magazine in America clearly would have had trouble.92

The editorial also asked readers to tell friends, newspapers, radio stations, and congressmen about the situation, and it pleaded for new subscriptions.

While many publications discussed Scanlan’s’ victimization, few actually reviewed Volume One Number Eight. Anthony Wolff wrote in the January 25, 1971, issue of Newsweek that readers “whetted by the publicized delay may be disappointed” and noted a “lack of editorial commitment to the revolutionary struggle.”93 He criticized the “Guerilla Attacks in the United States” section, which he deemed a “dry tabulation of events from bombings of Selective Service centers to more ambiguous acts of vandalism that Scanlan’s sometimes generously interprets as in the guerilla spirit.”94

Wolff’s Newsweek review was possibly Scanlan’s’ last. The magazine was nearly penniless; the printing delays had cost Scanlan’s more than three months of newsstand sales and new subscriptions, too much to bear for a magazine that relied solely on income from those sources. “Once we were wiped off the newsstands,” Zion later wrote, “it was obvious we were finished.”95 Scanlan’s’ directors voted overwhelmingly for bankruptcy, despite Zion’s attempts to sell the magazine and Hinckle’s effort “to keep the magazine going at any cost.”96

Zion wrote in Read All About It! that the pressure of struggling to print the eighth issue destroyed his friendship with Hinckle. If Zion wanted to repair that relationship, he did himself no favors later in 1971 when he divulged that Daniel Ellsberg was the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times.97 Hinckle and former managing editor Humber responded to what Zion had done by issuing a joint statement that read, “Sidney Zion’s reprehensible act is that of a publicity-seeking scavenger.”98 Hinckle and Humber were not the only persons whose relationship with Zion soured following Scanlan’s demise. Thompson wrote Zion a scathing letter in February 1971, calling him a “worthless, lying bastard” for refusing to pay him the $3,400 Hinckle had agreed Scanlan’s owed Thompson in fees and expenses.99 Thompson called into question Zion’s value to Scanlan’s:

What the fuck would you know about Scanlan’s dealing with writers, financial or otherwise? The only interest you ever showed in the magazine, as I recall, was that useless, atavistic series on ‘dirty kitchens’ that was a constant embarrassment to the magazine. . . . As far as I or the other writers were concerned, Hinckle was the editor & you were some kind of two-legged nightmare to be avoided at all costs. . . . You never knew anything, Sidney. You were humored. . . . In ten years of dealing with all kinds of editors I can safely say I’ve never met a scumsucker like you.

You’re a disgrace to the goddamn business and the only good thing likely to come of this rotten disaster is that the name Sidney Zion is going to stink for a long, long time.100

Thompson was far kinder to Hinckle in a February 28, 1971, letter to Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, in which Thompson proposed a critical article titled “Farewell to Scanlan’s” (it was never written):

Hinckle was the only editor in America you could call at 3.00 a.m. with a sorry idea & feel generally confident that by the time you hung up you’d have a $1500 story in your craw, plus massive expenses & whatever else you needed to get the thing done.101

Scanlan’s managing editor Don Goddard once called the magazine “the ignis fatuus (foolish fire) of liberal journalism.”102 Foolish or not, Scanlan’s was taken seriously enough by the U.S. government to attract its attention and apparently its ire. And there’s little doubt that government intervention contributed to Scanlan’s’ downfall. In Read All About It!, Sidney Zion seemed proud that it was the special attention of “The Nixon Gang” that helped shut down the magazine:

We were plenty aware of the trouble the Nixon crowd was causing us, only we couldn’t convince anybody in the news media; they thought we were broke, paranoiac, or both. Again, this was long before Watergate; who would believe that the President of the United States would bother to go after what John Dean called a ‘shit-ass magazine’? . . . Enough for me that Dean said Nixon was after us—at least now nobody could tell me that I was some kind of nut. The Nixon Gang had put us away, a precursor to Watergate, and who can gainsay it?103

Zion also wrote that he was “proud” of Scanlan’s’ achievements, and looked back with fondness on the magazine’s experience:

[T]he point is we stayed true to our dream. We combined muckraking with literature and laughs—always there with laughs. Which is how Hinckle and I started. . . . [T]hough the laughs ran out for Hinckle and me, I drink to us every year on the anniversary of our death. To Scanlan’s, not to Warren, not to me, to Scanlan’s.104

Hinckle, on the other hand, appeared ambivalent about Scanlan’s when writing about the experience in Lemonade, and suggested his heart was never quite in it. “Like a toy soldier running down,” Hinckle wrote, “I went through the motions of launching a new venture for the seventies, but the spirit wasn’t there, even if the money was.”105

Neither Zion nor Hinckle abandoned journalism following Scanlan’s’ passing. In fact, both men are still active columnists; Zion contributes to the New York Post, while Hinckle writes a twice-weekly column for the San Francisco Examiner. Hinckle, never one to shy away from controversy, was censored by the Examiner in 1991 after writing a column criticizing the Gulf War.106 Twenty years after Scanlan’s’ demise, controversy—and censorship—continued to follow Warren Hinckle.

William Gillis (@wcgillis) completed the Ph.D. program in the Indiana University School of Journalism in June 2013. He currently serves as Editor of The American Historian, a publication of the Organization of American Historians.

This article originally was presented as a conference paper at the 2004 Conference of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication and is available online from Michigan State University here.

The first eight issues of Scanlan’s Monthly are available for purchase for $1200 here.

by @liamk. This site uses affiliate links when linking to iTunes or Amazon.